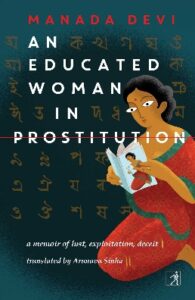

‘An Educated Woman in Prostitution’ by Manada Devi is a lost Bengali classic in the lines of well-known novels/ cinema like Umrao Jan Ada, Pyaasa, etc,. The protagonist of the novel is a feisty talented prostitute/courtesan.

Manada, Maani didi, Feroza Bibi, Miss Mukherjee – are the different identities of the one charming courtesan whose fascinating life story takes her from her wealthy cossetted upbringing to a life of debauchery and prostitution after she elopes with her married lover when in her mid-teens. She is capable, attractive and doesn’t ask for pity as she struggles with illness, poverty and abandonment, but ensures that she emerges relatively unscathed and carves a niche for herself in her profession.

Manada describes her colourful life with relish but is often introspective as she places her own position as a sex worker in the context of the times, calling out young sanctimonious patriotic men who maintain a high standing in society yet secretly fancy prostitutes.

The book (memoir) was first published in 1920 and was sold out within four months. It is translated into English by Arunava Sinha for publishers Simon & Schuster.

This extract from the book is a peek into the early life of Manada as she grooms to be a prostitute.

Rani Mashi taught me several tricks, demonstrating various styles of dressing, how to stand, ways of speaking, the manner in which to walk, the entire way of conducting myself so as to attract men. Even through misery and despair I had to smile at strangers, and be so flirtatious that no one could tell it was feigned. I learnt how to hold a glass to my lips, pretending to take sips, in case my lover was addicted to drinking. With lechers, each of them had to be given the kind of enjoyment they demanded. As I trained myself to deceive in this fashion, it seemed to me that a new Manada was being born within me.

I could sing well, and my voice was pleasing, as I have mentioned before. This is an art that serves prostituted women greatly. Rani Mashi engaged an ustad to teach me music; he said, ‘These patriotic and spiritual songs of yours will not work here, amongst prostitutes it’s lapeta or ghazal, or classical khayal or thumri. You can learn some kirtan too.’ I made considerable progress in a matter of three or four months with most of these, although the kirtan took me longer.

Along with the skills for deception, I also had to learn how to size men up. We had to be able to tell from someone’s face whether he was planning to steal from me or was afflicted with a foul illness, whether he was evil or a good man. I got into trouble too sometimes, for there were men who robbed prostituted women and even murdered them at times. The prostituted woman had to ply her trade with her life always at risk. For a mere two rupees or five a woman had to admit a stranger into her room—and the treacherous man could well stab her in the breast with a dagger and make off with her jewellery, leaving the wretched creature to die. It was not unknown for women in prostitution to be punished for their sins in this manner.

There was a gentleman who used to visit me, an eminent doctor of the city. It seemed he was not married at that time. I benefited greatly because of him; he gave me excellent medicines. He was extraordinarily good as a doctor, paying the fee for having someone like him treat me would have been beyond my means. He gave me ten or even twenty rupees whenever he spent two or three hours with me. Sometimes he took me for a drive in his car in the evening—we would stroll around the Grand Hotel, the bank of the Ganga, or Eden Gardens, and return late at night, whereupon he would give me fifty rupees. His largesse brought me nearly two hundred rupees a month.

Rani Mashi used to warn me, ‘Earn as much as you can, while you can, ma. Keep your old age in mind. If you do not save now you will suffer afterwards, as you can see, no one in this profession has any friends. Money is all you will have.’ The generosity of the doctor had made me less diligent when it came to making money from other clients, but Rani Mashi knew only too well he wouldn’t be there forever. Her surmise was not wrong. That year, 1915, there was a great cyclone in East Bengal in the month of Ashwin, in which many people were killed, and houses, gardens and crops were destroyed. A relief fund was started in Calcutta to alleviate their suffering, with the famous barristers Byomkesh Chakraborty and Chittaranjan Das (both dead now) leading this noble mission. Their efforts led to thousands of rupees being collected. Young men walked on the streets, singing and gathering money; they visited the prostituted women’s quarters too, and we contributed to the best of our abilities. One day my doctor babu told me, ‘Maani, it will make Mr C.R. Das particularly happy if all of you can make a collection and contribute the amount to the East Bengal Cyclone Fund. He would like all levels of society to respond to this noble cause. Do you think you can do it?’

I said, ‘I’m new in this field, I do not know everyone personally. If I have your support I will try my best.’ He said, ‘I know some more women in Rambagan and Sonagachhi and Phulbagan, theatre actresses can be included too.’

Apparently the doctor was already acquainted with Mr C.R. Das. Because of his own and some of his other friends’ efforts, the contribution of the women in prostitution amounted to over a thousand rupees. This was my first involvement in a public cause, and it gave me an opportunity to feel Mr C.R. Das’s touch on me. Tears of joy rolled down his cheeks when we bent over his feet and laid the bundle of currency notes. He gave us his blessings with his hand on our heads; I realised why he was called ‘Deshbandhu’.

Extracted with permission from Simon & Schister Publishers, India