Natural Cotton Varieties like “Gollaprolu Red Coloured Cotton” and “Kondaparthi Cotton” of Ponduru are almost extinct. Here is a story of Ramesh Ramanadham trying to revive these local varieties by ARUNA RAVIKUMAR

Today desi cotton, which has traditionally been a multi-crop using only 2% of water compared to inorganic cotton is unfortunately less than 5% of the cotton cultivated, with the rest of the 95% being BT cotton

In the rustle of silk and the fine count of handwoven sarees of India lies a skill that dates back to 5000 years with looms producing cloth that wove together a heritage of India’s rich culture and tradition.

Replete with numerous styles from different regions reflected in the unique design, vibrant colours and skilled use of warp and weft, our handlooms provide us with a distinct identity all our own. A series of developments over time beginning with the all -important process of cotton growing has however contributed to the gradual destruction of an ecosystem nurtured for centuries. The benefits of BT cotton in the country introduced in 2002 have been modest and short-lived and at the cost of indigenous or desi varieties like the Gossypium arboretum, which was the most common strain cultivated until the beginning of the 20th century. Today desi cotton, which has traditionally been a multi-crop using only 2% of water compared to inorganic cotton is unfortunately less than 5% of the cotton cultivated, with the rest of the 95% being BT cotton. Further, the overwhelming use of power looms across the length and breadth of the country, the fetish for mass production and the imitation of handloom designs on synthetics at lower prices may sound the death knell of handlooms and soon add it to the list of endangered ancient crafts in our country.

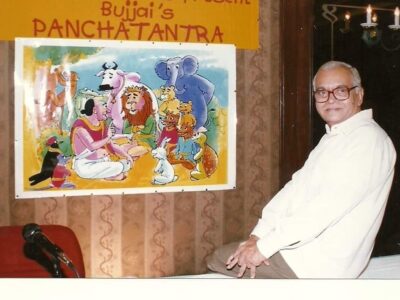

Ramesh Ramanadham

Ramesh Ramanadham, a specialist in handlooms, handicrafts, natural dyes, natural fibres and revivalist of natural coloured cotton has been working for more than three decades for the preservation of handlooms through his organization R.S. Crafts. He laments the fact that there are less than 500 handloom weavers weaving traditional Tussar silk across Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, Chattisgarh, Bihar, West Bengal and the North East – who practice the craft in its purity. “Today 98% of fabric that passes as Khadi is not traditional Khadi. Many Tussar silk sarees sold in the market are in fact mulberry silk imported from China and Korea, coloured and passed on to customers as Tussar silk. Traditional Khadi silk involves the process of withdrawing the silk yarn from the cocoon manually and twisting the silk thread on the thigh through a process called “false twisting”. Telangana has its own variety of Tussar silk but less than 15 weavers are engaged in weaving in the traditional way” he points out.

Government intervention through policy decisions can provide both livelihoods to tribals and prevent handloom from becoming a languishing skill. It will save Indian weaves and indigenous natural dyes, which are unmatched in the world. “How many of us have noticed how the colours in the ancient cave paintings of Ajanta and Ellora have remained vibrant over the ages or how the beautiful colour from the Shankha pushpi flower used in ancient times is mistaken for the better known indigo dye. Why do we need to import manjishta and ratanjot for dyeing fabric if we have enough supplies of indigenous dyes?” Ramesh questions. Livelihood to tribals in the forest regions of India through the cultivation of Terminila Arjuna (Tella Maddi), Terminalia elliptica (nalla maddi) trees in the deep forest region where silkworm collection through cocoons for Tussar silk also known as wild silk is abundant, provides livelihood to the tribals. And, this promotes the much needed silk yarn which is the basic material for weavers. Similarly, Ari, Moga and a number of varieties of silk can be procured from the forests.

Ramesh has been working to re-establish the Khadi ecosystem by bringing technology into the sales part and ensuring proper remuneration for the weavers

Craft tourism is also a concept with much potential where people from the fashion industry and those interested in knowing more about cotton and silk weaving, can visit forests and see first- hand the entire process from procurement to the final product. Alarmed at the prospect of losing skills that have been a part of our hoary civilization not-for profit organizations like ‘Tula’ in Chennai, are bringing out desi cotton garments with the yarn spun by skilled Khadi workers, which are also coloured with natural dyes. Ramesh has been working to re-establish the Khadi ecosystem by bringing technology into the sales part and ensuring proper remuneration for the weavers. One of the most important tasks undertaken by him is the revival of the “Gollaprolu red coloured cotton” and’ Kondaparthi cotton’ of Ponduru which are natural coloured cottons that have become adulterated. These are but two varieties from the hundreds of local varieties that are now almost extinct.

“Gollaprolu Red Coloured Cotton” and “Kondaparthi Cotton” of Ponduru which are naturally coloured cottons are but two varieties from the hundreds of local varieties that are now almost extinct

Apart from procuring seeds of local varieties from different regions and growing natural coloured cotton Ramesh Ramanadham is doing his bit to increase consumer awareness about handlooms and handicrafts through talks, workshops and documentation of our rich handloom heritage. He plans to hold an exhibition of handloom sarees used over generations in different regions of the country in 2024 for which he has started the process of sourcing pure handloom sarees and dhotis that are a rarity in present times. “Every saree has a story, an emotion, a sentiment associated with it. By showcasing beautiful weaves that have stood the test of time I seek to inspire people towards reviving the craft” says Ramesh who networks with likeminded people who take pride in our tradition and place skill above all else. Kalamkari work, Cheriyal dolls and bell metal craft are other areas that he is working on. Getting back to our roots and nurturing an ecosystem that brings back our past glory is an easily achievable task if government and individual effort coalesce towards this goal. Hope looms large in this direction.

Ramesh Ramanadham can be contacted at rskrafts@gmail.com