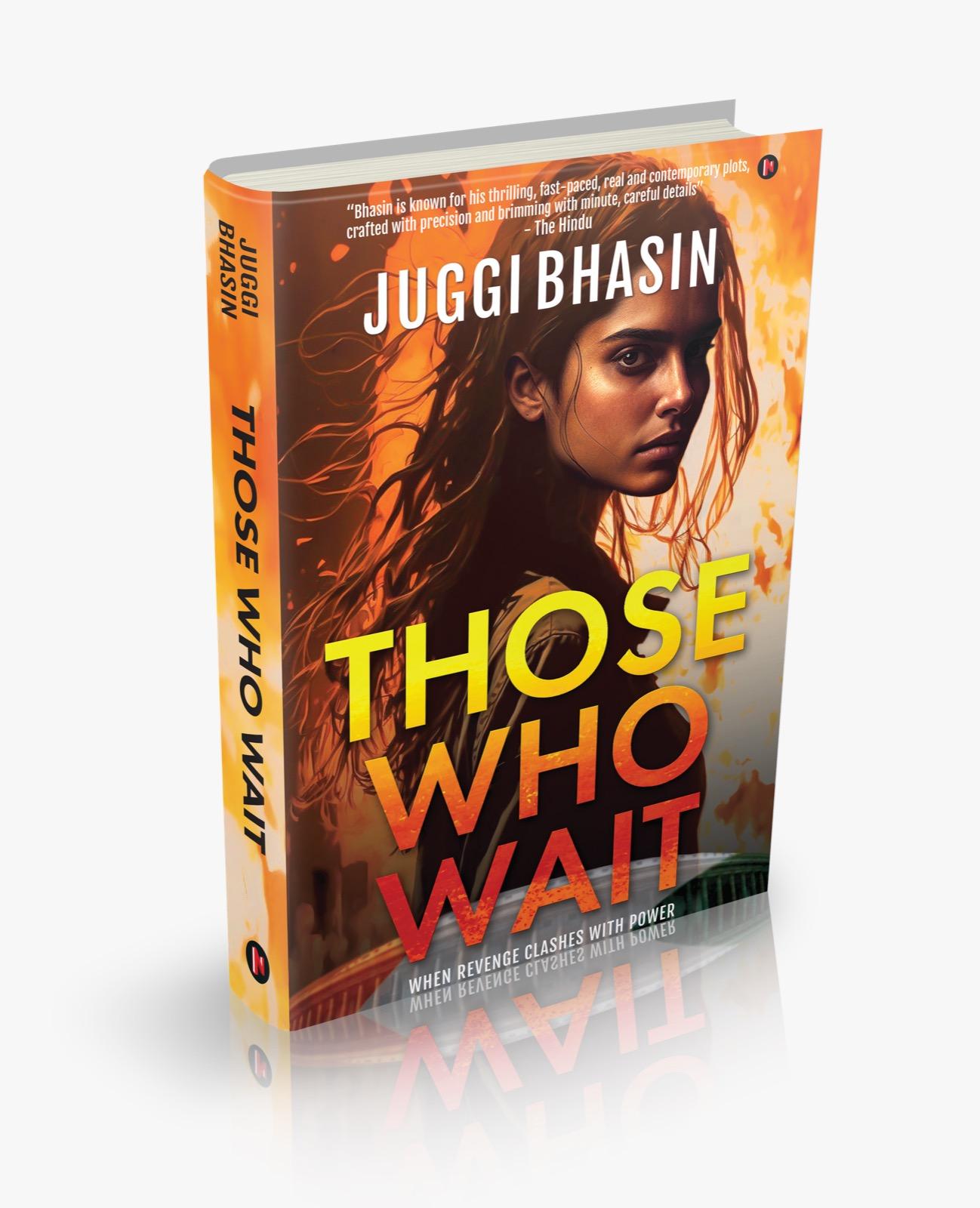

Unveiling of ‘Those Who Wait’: Juggi Bhasin’s Latest Literary Creation”

What unfolds when patriotism conflicts with familial allegiance? Who is Samyukta, and why is her life’s mission to disgrace Kanwar Pratap Singh, the highly successful Indian Prime Minister? How do decorated army officers, Aseem and Ranbir Tripathi, end up on opposing sides of their beloved nation? How does Sonali Tripathi, Ranbir’s sister, become entangled with the Maoists? Are the Chinese successful in humiliating India?

All of these questions find answers within the pages of ‘Those Who Wait’. The book takes readers on a journey that grants them an intimate look into the lives of influential figures, offering a captivating and involving narrative that draws readers into the fictional characters’ experiences.

Ultimately, ‘Those Who Wait’ is a narrative that tells the tale of individuals who, alarmingly, could exist in reality.

Juggi Bhasin stands out as one of India’s earliest professionally trained television journalists. His career at Doordarshan News as a senior news correspondent has encompassed pivotal events such as the 1992 Babri Masjid demolition and reporting from Kashmir during a turbulent period of militancy and insurgency. Notably, in 1992, he became the first Indian TV journalist to interview North Korea’s supreme leader, Kim Il Sung, in Pyongyang. Juggi also contributed significantly to Lok Sabha TV as a core team member and lead anchor.

In the realm of literature, Juggi made his writing debut in 2012 with the critically acclaimed and successful thriller, ‘The Terrorist’. This debut was followed by four more well-received books, all published by Penguin Random House.

Here’s an extract of a story from Juggi Bhasin’s ‘Those Who Wait’

29

Good Cop, Bad Cop

The two-word slogan ‘LEFT OUT!’ at first glance appeared innocuous, almost harmless, an ironic, two-word summary of the prevailing leftist sentiment prevailing at JNU. But appearances were deceptive. The slogan was like a grenade thrown into the body politic of the nation, waiting to explode.

It swiftly gained traction amongst the young, and soon became a war cry of the marginalized and the dispossessed, wilting against real or imagined oppression; it became the inspirational opening words of the Magna Carta of political opportunists who had been defeated in elections but nevertheless used the slogan and the campaign to jockey into positions of power.

At the very least, the slogan reverberated with the idealistic left, left of the centre young who felt they had been trampled under the boot rule of a hidebound, geriatric, right-wing government. All kinds of grievances bubbled up to the surface and the slogan offered multiple meanings to different sets of people. It offered abundant possibilities of the prefix, and soon, rebellious groups looking to fish in troubled waters took out marches and held

rallies with incendiary slogans like ‘MUSLIMS LEFT OUT!’, ‘DALITS LEFT OUT!’ ‘FARMERS LEFT OUT!’, ‘MIGRANTS LEFT OUT!’.

The result was daily mayhem on an industrial scale. In the beginning, Shonali and a core band of insurrectionists co-ordinated the student volunteers orchestrating the revolt. Soon, the movement got so big that autonomous units spread the message of revolt and insurrection all over the country. A month into the rebellion and it seemed as if the “LEFT OUT” campaign had descended into a gruelling match between a marginalized country and an elite, prosperous, yet relatively small set of people.

The movement was, in a sense, a repeat of the failed left movement of the sixties and seventies, but it was succeeding in the present because the packaging this time was sexy, new age, and appealing to the young. Besides the catchy slogan, the dress code of the “LEFT OUT” stormtroopers and keepers of the faith was chic, urban-eye candy. The activists would dress in all black denim, each sporting a backpack, tennis shoes, cap, and black masks covering their noses and mouths, emblazoned with the fluorescent legend of ‘LEFT OUT!’ At any rally or gathering, the stormtroopers would start stationary jogging, signalling intent they were ready to ‘go’ and effect ‘change’ and the war cry would ring out, ‘LEFT OUT, NO MORE!’

All that the formless but potent movement needed was a face to serve as a rallying point. Shonali working in tandem with Baisakhi created a profile of Bijoy that inspired a generation looking for new heroes. Millions of Bijoy posters flooded the streets which showed a Che Guevara revolutionary look of Bijoy with wind-swept hair, eyes that were fearless but compassionate, and looks that were tender yet ferocious. Impressionable girls wept at the sight of his posters and boys looking to emulate would copy his windswept no-time-for-a-haircut look.

It was a time of great ferment, and Shonali made sure to operate behind the scenes and stay out of the limelight even as she created a trail-blazing dark path. The government, caught completely by surprise by the trajectory and spread of the campaign, responded as most governments do in such situations.

Their moves were leaden-footed cliched, offering outdated solutions and threatening rhetoric. Such a response fuelled the movement even more till sensible and astute voices in the government advised caution and more sure-footed responses.

The crime branch cell of Vasant Vihar Police Station in Delhi, using intelligence sources inside the JNU campus, soon figured out some of the leaders and projectionists spearheading the movement. On a Sunday morning, as Shonali was setting the table for an aloo parantha and curd breakfast, there was a knock on the door. Laxmikant Tripathi opened the door and stared at the Station House Officer and a female assistant sub-inspector at their doorstep.

‘Yes?’ inquired the war veteran.

‘Myself Purshottam Lal, SHO, and ASI Madhu from Vasant Vihar Police Station. We have some questions for Miss Shonali.’

Shonali at that moment walked into the dining room with a casserole containing aloo paranthas. A barely concealed look of displeasure clouded Laxmikant Tripathi’s face.

‘Questions for Shonali? You must be mistaken. You must be confusing her for some other person. The competence of our police force is legendary.’

‘No, mistake Uncle Ji. We have a job to do.’

‘I am not your Uncle Ji!’

The senior cop persisted.

‘We can have a civil chat now, or else, she will have to come to the police station for questioning. Your choice.’

Shonali came to the door and deftly guided her father away from the door before he blew a gasket.

‘Come in and do your job. I have nothing to hide here.’

The senior policeman came in and sat on the sofa without an invite and carefully looked around the modest apartment while taking out a notebook. The ASI sat in a corner chair and grimly looked at Shonali with her best, tough cop stare. The senior cop questioned Shonali.

‘Okay, Shonali madam, we believe you are studying at JNU. We have reports that you are one of the ringleaders of this “LEFT OUT” agitation. What do you have to say to that?’

‘Complete nonsense. JNU is not a primary school functioning under a school principal. All of us are mature scholars, and like most mature people, we have a certain political and social view of things. We have every right to express it. Last I knew, the

Constitution gives us the right to express dissent.’

‘Madam, that might be correct, but you have no right to burn buses, commit arson in universities, or destroy the social order. You might have read about your handiwork in the papers. Four people have been killed in this agitation so far.’

‘You are assuming too many things here. In the first instance, what proof do you have I am one of the leaders of this agitation? Secondly, how are these four deaths connected to me?’

The ASI noisily shifted in her chair and challenged Shonali.

‘Shonali Devi, our Sahab here is a very patient man. Perhaps too kind-hearted. We have all the proof we need. You had better start cooperating with our investigation, otherwise, it will go very badly for you!’

Laxmikant Tripathi almost burst a vein at the insinuation. He screamed at the ASI.

‘How dare you! How dare you come to my house and accuse my daughter! Do you know who I am? You are worthless police trash! You think I am not familiar with these tactics? This good-cop-bad-cop routine! A thousand ex-servicemen will march to my door if I give the call. Get out! Get out of my house right now!’

The senior cop stood up.

‘Calm down, Uncle Ji! You will burst a coronary if you don’t watch out!

‘Papa, let it go!’ screamed Shonali.

But Laxmikant Tripathi was experiencing a paroxysm of fury like nothing he had ever experienced before.

‘Get out! Get out! I will beat both of you with my bare hands. The filth that you are….’

And then, suddenly, Laxmikant Tripathi was airborne. His face looked flushed and quite stunned as a powerful, debilitating force flung him over the sofa to a corner, making the embittered soldier gasp for breath and frothing at the mouth, his life hanging in balance