Rocks of the Deccan from Hyderabad in Central India, to Hampi in the South – their in depth exploration gave way to Sudeep Sen’s next…Rock…which completes the larger eco-trilogy by poet, writer, editor, translator, and photographer, Sudeep Sen.

The new work in Rock — emerges from my dedicated trips to Khajaguda Hills and other Deccan rock scapes in and around Hyderabad – the poet speaks about his inspiration for his latest work during a conversation with poet, academician Jhilam Chattaraj

on the ocassion of World Earth Day on April 22

[Photograph by Dinesh Khanna]

Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in,

where nature may heal and give strength to body and soul alike.

— John Muir, The Yosemite (1912)

The world is burning — heatwaves, floods, pandemics. We witness the collapse but consumed by the burden of our banal responsibilities, we defer the change. Most of us are aware of the consequences of climate change, but we rarely apply sustainable habits in our daily lives — even separating dry and wet waste is too onerous a burden to carry. Activists, writers, poets, artists, and pro-environment crusaders, however, have refused to be mute witnesses to this damage; each one is doing their bit to raise awareness about impending natural disasters.

In recent years Sen has carved a niche in the subgenre of ‘Anthropocene’ poetry in the English language, both in India, and internationally. His depiction of the changing natural scapes is cautionary, precise and detailed, yet hopeful. Sen has been writing about sinking islands, melting ice caps, the felling of trees, and the vanishing symphony between man and nature, for many years.

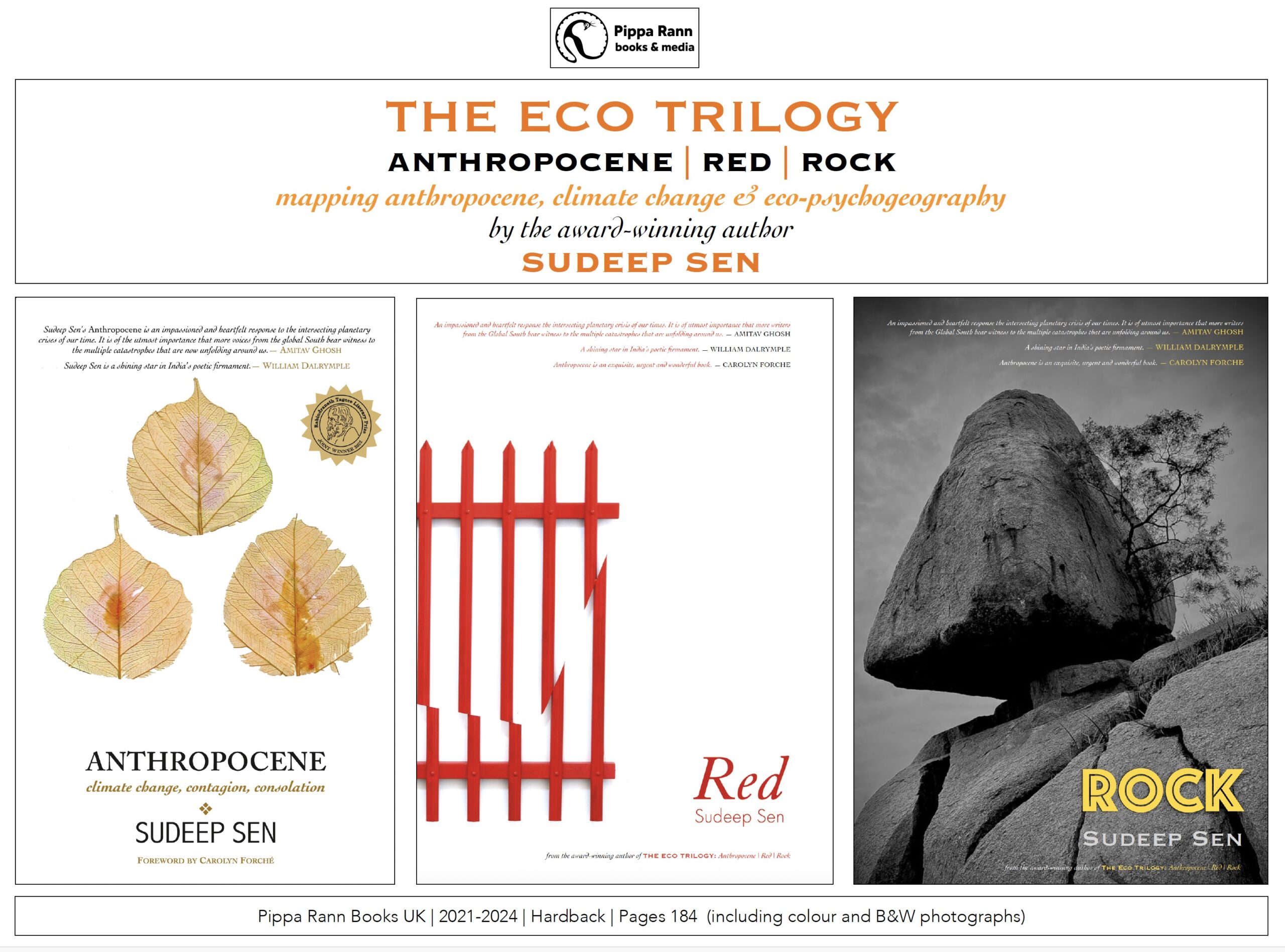

However, his vision of the earth and its future materialized and led to his recent, ‘The Eco Trilogy’ — Anthropocene: Climate Change, Contagion, Consolation (Pippa Rann Books UK, 2021); — Red (Nirox Foundation, South Africa, 2023), a creative response to the ecotones and the wider ecology in and around South Africa’s Nirox Foundation and the Cradle of Humankind; — Rock (forthcoming, Pippa Rann Books UK, 2023-24), an ekphrastic exploration of rocks of the Deccan from Hyderabad in Central India, to Hampi in the South.

Over the years, Sen has nurtured an organic relationship with poetry. Art, photography, music, dance, culinary cultures, geological wonders — everything has led him to create an empire of words — poems with fantastic architecture — word castles inviting curious readers to experience life through Sen’s poetry. Although Sen is often caught saying, “poetry is a mental disease” yet, anyone familiar with Sen’s work would know that Sen has offered poetry as a healing potion to the world.

We speak to Sudeep Sen about the way he uses language as a tool to raise awareness about the environment; the process by which he decodes nature’s intricate structures to write poetry, and how sustainability is not just in writing but an everyday practice.

What is it about the environment that draws you to respond through poetry?

How can one not respond to one’s own, and the wider environment — one is perennially surrounded by it, impacted by it — its geography, contour, vegetation, mood, colour, texture, climate. It seeps into our personal lives, dictating and defining our inner worlds. Samuel Beckett puts it succinctly, with his inimitable humour and irony, “You’re on earth. There is no cure for that.” As an artist and individual, I have no choice but to respond to it with the resources at my disposal — creativity, craft, intellect, and activism.

Congratulations on winning the Sanatan Puraskar Lifetime Achievement Award for Literature, 2024! We know the Sanatan Sangeet Sanskriti was founded in 1990 by Dr Kulwant Rai, Shri N K P Salve, Shri Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Justice V B Eradi, Pandit Birju Maharaj, and Shri M N Krishnamani, who shared their love for the arts and literature. What does the award mean to you?

Thank you. It is simultaneously humbling and pleasing. And especially meaningful when the array of jurors and people behind this award are leading professionals and personalities in their fields namely, Ashok Vajpeyi, former bureaucrat and poet; Rajeev Sethi, Chairman of the Asian Heritage Foundation; and Dr Quraishi, Former Chief Election Commissioner of India and chancellor of IILM University.

35 years of poetry — it’s almost unreal— do you have a ‘sorcerer’s stone’?

It might appear “unreal”, but in reality, it is simply an aggregation of a long-sustained innings of devotion to a craft — poetry is a vocation, a calling for me.

I notice that over the years you have simplified your material requirements — you wear the same set of black shirts or kurtas everywhere, every day — minimal like your poetry. In the context of ‘World Earth Day’, which primarily began as a movement in 1970 to ban the use of plastic, I am curious to know if you have any everyday habits that lead you toward a plastic-free, sustainable lifestyle.

Growing up — my family was fairly eco-conscious, without even knowing that they were (or before that term became trendy). We didn’t waste water or other forms of energy like electricity. Washable bags made of canvas or jute were used for daily shopping. We walked to the market. We barely had any plastic in our kitchen — everything was brass, copper, steel or glass. We didn’t waste — we recycled, and reused. And much of that remains the same even today. My life continues to be very simple on an everyday basis.

How do you wish to use poetry towards the social and cultural growth of the nation?

I don’t think I write poetry with a specific intent or purpose, such as social and cultural growth. If it achieves that, I am happy. Over the years, I have had people tell me that my poetry has influenced them individually and collectively, provided solace and insight, succour and courage. I believe good poetry has that power. My work as an anthologist has attempted to showcase the best of Indian poetry to India and the world. As a translator, I want poems to travel wider, cross-linguistic boundaries, and reach out to as many people as possible. I know poetry to be a lonely space — so I mentor younger writers and teach as a visiting professor at universities. But mostly I write. The rest happens organically — that is the inherent power of a good poem or poetry.

You see the world through the lens of language. Tomorrow, April 23rd is ‘World English Language Day’. How has English shaped your life?

It has shaped me in the most fundamental way without me being actually aware of it. My preferred choice of language for creativity, albeit rather instinctively, has been English — which I have always considered as an Indian language, a language I learnt from my parents and grandparents. Having said that, I do translate from Bengali, Hindi and Urdu. On a daily basis, I grew up in a tri-lingual family. In this poly-lingual space, quite organically, my ‘own’ English found its safe home.

What is the one thing you truly enjoy about the process of creation?

The wonder of it all! Every poem I write fills me with a sense of excitement and accomplishment.

Having written a poem, especially if it is a good one, I often wonder where it came from. Was it me — did I do it? Or did it just come through me? — was I merely the conduit? I feel this often, even now.

Is there anything you missed out on because of poetry?

Poetry has given me everything that truly matters. Anything it was unable to give, doesn’t matter.

In the book Anthropocene, you critiqued Covid-19 as a culmination of man’s long geological damage to the earth. In Red, you wove cultural, artistic, and geographical connections between Africa and India. What would be your perspective in Rock?

Rock architecture in the Deccan plateau in central and south India, part of the 2.5 billion years old Dharwar craton, are unique in hosting some of the oldest and most stable rocks and stone formations in the world. In Rock, I continue and stretch the eco-geological arc that started during the sojourn in South Africa’s ‘Cradle of Humankind’ and culminated in Red. This book expands its reach to include India in a more concrete manner — thereby inter-linking earth’s meaningful geographies and “climate imaginaries”.

Rock architecture in the Deccan plateau in central and south India, part of the 2.5 billion years old Dharwar craton, are unique in hosting some of the oldest and most stable rocks and stone formations in the world. In Rock, I continue and stretch the eco-geological arc that started during the sojourn in South Africa’s ‘Cradle of Humankind’ and culminated in Red. This book expands its reach to include India in a more concrete manner — thereby inter-linking earth’s meaningful geographies and “climate imaginaries”.

The new work in Rock — emerges from my dedicated trips to Khajaguda Hills and other Deccan rockscapes in and around Hyderabad; the crumbling remains of the Rachakonda Fort in the eponymous village and the incredible boulder-speckled hilly landscape that surrounds it; and to the spectacular stone-art, rock temples, and litho-formations in and around Hampi.

Rock completes the larger eco-trilogy (that started with Anthropocene) — written during the pandemic in 2020-21; Red — written in a frenetic trance-like state while I was on a three-month artist/writer-in-residence fellowship at South Africa’s Nirox Foundation in 2023.

My residency there and my sojourn in the Cradle of Humankind (and thereafter in the Deccan craton belt in India), have shifted something fundamental in my inner core. My relationship with nature, its elements and forces — rocks, soil, sky, water, animals, birds — have become even more intimate, intense and visceral. This in turn, of course, has affected my writing.

Integrating back into the noise of urban living has been a challenge and I often chafe at the demands of the city. In such moments, I remind myself of the words of the Botswana san mystic healer, Tsitano Maburunyara — “In a trance I can change myself into a star and visit my friends in the sky …. And when I return, I drop to the ground and become a person again.”

Even though you are in the prime of your life, you often say that there is so much more to do or achieve. Do you have any specific literary goal in mind?

The goal is to continue writing, getting better and better with every book, and staying inspired. Just living with poetry is such a pleasure and a privilege.