Netaji Bose, who led the Indian National Army to wage battles against the British, allegedly died in an air crash in Taipei, Taiwan soon after the Second World War came to an end. Did he really die in the air crash or was it a fabrication? This question was considered by three inquiry commissions, the last of which came to the clear conclusion that there was in fact no air crash. Each report is carefully dissected by the author, a trained international lawyer and public intellectual, Rajesh Talwar in his book – The Vanishing of Subhash Bose: The Mystery Unlocked.

In the book, the author explores – If Bose did not in fact die in the air crash, where did he go, what happened to him, and when, where and how did he meet his end? Why did Prime Minister Nehru keep Bose-related files away from the first committee that conducted an enquiry? Why did India’s first prime minister order that surveillance be carried out on the Bose family for decades? Why did Prime Minister Morarji Desai speak of new evidence that challenged the conclusions of the first two inquiries that Bose had died in an air crash? Why did Desai subsequently fall silent? This book provides explanations of all the important questions that have plagued Indian minds for decades.

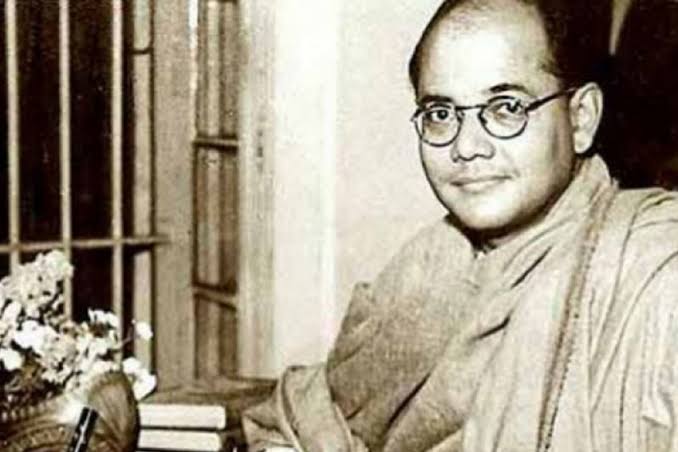

Here’s an extract from the book published with permission on the occasion of his birth anniversary

THE WISH TO BELIEVE NETAJI SURVIVED THE CRASH AND BECAME A SADHU

Of the four theories discussed three prominent theories have him adopt the garb of a holy man or a sadhu. This would appear to tell us more about India and the people who wished to see Bose alive than about Netaji himself. Even when the sadhu himself repeatedly denied being Netaji as was the case with the Shaulmari Baba people continued to insist that he was Bose and was concealing his true identity for a purpose!

Of the four theories discussed three prominent theories have him adopt the garb of a holy man or a sadhu. This would appear to tell us more about India and the people who wished to see Bose alive than about Netaji himself. Even when the sadhu himself repeatedly denied being Netaji as was the case with the Shaulmari Baba people continued to insist that he was Bose and was concealing his true identity for a purpose!

Millions of Indians admired and loved Mahatma Gandhi, but in this vast populous nation of ours, there were also millions, especially among the younger generation who thought of him as an old man with impractical ideas. Gandhi to them was saintly, but boring; Bose on the other hand was younger, dynamic, handsome and dashing. Millions looked to Netaji Bose as an alternative. This was the man they truly admired. While Netaji was a national leader, undoubtedly he was yet a bigger hero in his native Bengal.

The great psychologist Sigmund Freud wrote about how people often believe what they wished to believe. The converse of this is also true: people also try to disbelieve what they do not wish.

When a man such as a Netaji dies, he dashes the hopes and aspirations of so many who looked up to him as their ideal. All these people wished with all their heart that he was still alive

When a man such as a Netaji dies, he dashes the hopes and aspirations of so many who looked up to him as their ideal. All these people wished with all their heart that he was still alive. Others were there who wished to say that he had been alive in the new incarnation of Shaulmari Baba, or Gumnami Baba aka Bhagwanji and they had met with him and spoken to the great man.

When a man such as a Netaji dies, he dashes the hopes and aspirations of so many who looked up to him as their ideal. All these people wished with all their heart that he was still alive. Others were there who wished to say that he had been alive in the new incarnation of Shaulmari Baba, or Gumnami Baba aka Bhagwanji and they had met with him and spoken to the great man.

It’s a case of ‘suspension of disbelief’ feeding into the old Hindu idea of a person going into vanashram in his later years, cutting himself off from society,

in order to understand the true nature of this existence, and contemplate the Divine. The world itself is maya, a mere illusion. This also becomes the perfect explanation for why he had not come out into public life.

During his younger days Subhash Bose was much taken up by the Indian mystic, Vivekanand.243 In later years he discovered Freud, and unlike Gandhi immediately understood that sexual repression by itself was not something saintly. As the historian Leonard Gordan writes many would like to believe that Subhash never married or that he was celibate and became a spiritual guru in his later years. This fits in, he writes, with the myth building culture in India.

There is of course one other reason why the Sadhu in disguise story fits in so well with Netaji’s personal history and life. Aside from his leaning towards spiritual matters since an early age, in his later revolutionary years, Subhash become a master of disguise, when he left Calcutta in 1941, dressing up as a Pathan while traversing Afghanistan and changing his disguise to that of an Italian businessman once he was in Russia.245 So disguising himself as a Sadhu, in a way, merged both public perceptions of him: as a man with spiritual if not saintly inclinations but also a master of disguise and subterfuge.